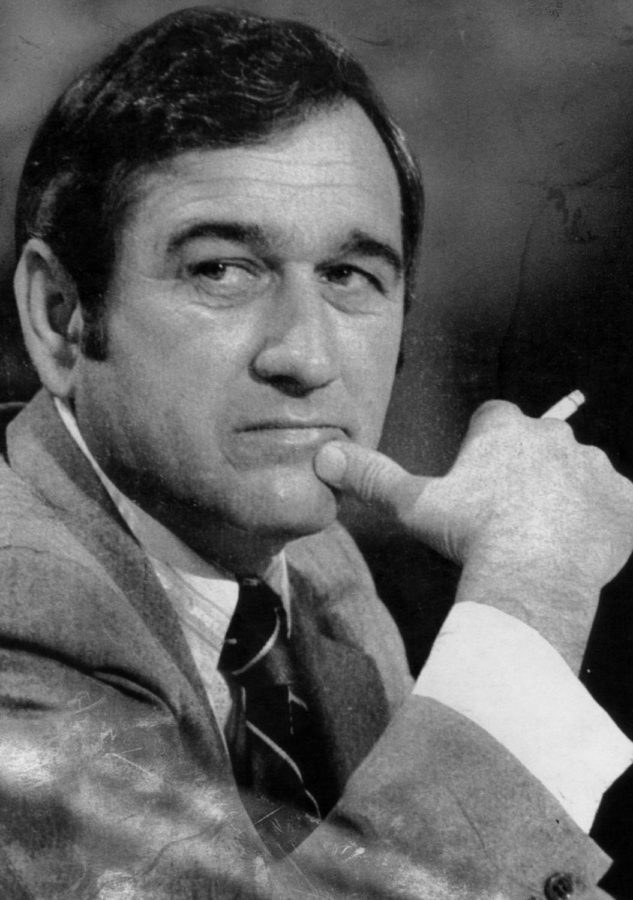

The Saga of Ray Blanton

It is often said that absolute power corrupts absolutely. Those who seek power often pursue it genuinely, seeking to serve the people and make improvements to their lives. However, in that pursuit people often fall victim to faults of human nature such as greed, ego, and corruption. The story of Leonard Ray Blanton, Tennessee’s 44th governor, is such a story. To say he is a complex individual is an understatement, and his story is one of dramatic rise and abrupt fall.

Early Life

Ray Blanton was born on April 10th, 1930 to an impoverished sharecropping family in rural West Tennessee. Living in a dilapidated cabin on a cotton patch, Blanton became familiar with poverty at a young age. After a few years of raising cotton and living in squalor, Blanton’s family formed a construction company to build roads in rural West Tennessee and North Mississippi. During his rough-and-tumble youth, Blanton would often visit sawdust-floored juke joints, where he amassed a collection of scars, scrapes, and scuffs. After graduating from Shiloh High School in 1948, Blanton studied agriculture at the University of Tennessee, receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1951. He then taught at an Indiana high school from 1951-1953, returning to Tennessee to work in his family’s construction business.

Congress

Blanton’s background provided him with a rough-hewn, populist appeal, and Blanton decided to pursue politics. In 1964, Blanton was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives, where he served one term and was often seen sitting near the back of the house chamber sporting a pair of sunglasses. Following a single term in the TN House, Blanton ran for the United States House of Representatives in 1966, and was successfully elected, exploiting his charisma and “working man” background. Blanton would represent Tennessee’s 7th congressional district from 1967-1973, a total of three terms. During his time in congress, Blanton had poor attendance, sponsored few bills, and served on just two committees: the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, and the District of Columbia Committee. Rather than focus on these activities, Blanton prioritized his constituents, spending copious amounts of time responding to voter concerns. He also often met with and spoke with students. In 1970, Tennessee lost a seat in congress due to the new census, and Blanton’s seat suddenly became far more competitive due to redistricting. Thus, in 1972, Blanton ran for the United States Senate, ultimately losing to popular incumbent Howard Baker. Not to be deterred, Blanton announced his candidacy for governor of Tennessee in 1974, running against Lamar Alexander (a former campaign manager for incumbent governor, Winfield Dunn, who was term-limited). Blanton, a Democrat, was at an advantage, as President Nixon and the national Republican party became enveloped in the Watergate scandal in 1974 (Nixon would resign in August of that year). Personal charisma, populist appeal, and his opponent’s connection with the scandalized party allowed Blanton to sweep into the governor’s chair.

Governor-The Good

On January 18th, 1975, Blanton was inaugurated as Tennessee’s 44th governor. As governor Blanton would prioritize tourism and foreign investment, creating the Office of Tourism (first in the nation), encouraging travel to and investment in Tennessee. In addition, Blanton made several overseas trips to recruit foreign investment. These trips resulted in Japanese, British, and German investors taking an interest in Tennessee, and Blanton’s first trip abroad resulted in a $10 million investment from the German firm Mahle, Inc, in a manufacturing facility in Morristown. Such investments paid dividends. Under Blanton unemployment in Tennessee fell from 9.6% to 5.6%, and over 64,000 new jobs came to Tennessee. In addition, in 1977, the new Office of Tourism helped to welcome 5.5 million new visitors to the state. Along with tourism and foreign investment accomplishments, Blanton also worked with the legislature to modernize Tennessee’s retirement system, making it one of the most fiscally sound in the country. Blanton promoted tax relief for elderly residents, and supported programs aiding African Americans and women. Despite these achievements, Blanton’s administration had a dark side, and was rank with corruption, patronage, and scandal. Blanton would go on to be Tennessee’s most controversial governor.

Governor-The Bad

As governor, Blanton would establish an extensive network of patronage officials, installing political allies in every country in the state. Blanton used this network to intimidate opponents, promote his administration, and consolidate power. Despite criticism, Blanton was unapologetic and insisted his political minions were merely “advisors”. In addition to extensive patronage, Blanton also spent lavishly, taking friends on trips on state expense and spending over $300 dollars on a single long distance phone call (a personal phone call). According to one report, Blanton and his aides spent $21,000 (taxpayer dollars) on personal phone calls, liquor bills, and limousine rental fees. In addition, Blanton accepted a controversial $20,000 pay raise and arranged for his family’s construction company to receive a lucrative paving contract at a state park. Blanton’s administration also became involved in the “surplus car scandal” of 1977, when officials sold surplus state-owned vehicles to political allies at reduced prices. General Services Commissioner Charles Bell would resign, and the Director of the Surplus Property Division, G.B. McCarter, was found guilty on two counts of embezzlement. Such scandals plagued the administration, and Blanton decided not to run for reelection in 1978. His former opponent, Lamar Alexander, would be elected that year. As Blanton’s term approached its end, the governor’s behavior became more erratic and temperamental, and his drinking (always a problem) intensified. Lashing out at the press and governing in an increasingly autocratic manner, Blanton was out of control. Furthermore, the greatest scandal of his administration was about to be exposed. In 1977, Marie Ragghianti, chairwoman of the state’s Board of Pardons and Paroles, was fired by Blanton when she refused to release prisoners who had bribed state officials in exchange for pardons. Soon rumors began to circulate about a “cash for clemency” scandal, and on December 15th, 1978, the FBI raided the Tennessee capitol and seized documents from Blanton’s legal advisor, T. Edward Sisk. Sisk and two other aides were arrested, and Blanton was forced to appear before a federal grand jury on December 23rd. Blanton denied any wrongdoing or involvement, and refused to resign in the wake of the scandal. On January 15th, days before the scheduled end of his term, Blanton issued pardons for 52 state prisoners, 20 of which were convicted murderers. One prisoner receiving a pardon was murderer Roger Humphreys, the son of a Blanton patronage associate. Blanton argued the pardons were part of an effort to reduce the state’s prison population. High-ranking government officials and the FBI suspected that the pardons were related to the recent “cash for clemency” scandal under investigation. Once state leaders were tipped off by U.S. Attorney Hal Hardin (a friend of Blanton’s)that the governor was planning more pardons, it was decided that Blanton had to be stopped in order to preserve the state’s reputation and prevent the release of more criminals. Thus, Tennessee Speaker of the House Ned McWherter and Lt. Governor John Wilder agreed to depose Blanton by swearing in Governor-Elect Lamar Alexander three days before the scheduled inauguration. This was possible because the Tennessee constitution was vague as to when the new governor could be sworn-in. Ultimately, Blanton was successfully removed from office in what Lt. Governor John Wilder later called “impeachment Tennessee-style.”

Later Life

Following his ouster, Blanton was found guilty of mail fraud, extortion, and conspiracy and was sentenced to 22 months in federal prison. Released in 1986, Blanton would desperately try to redeem his tattered reputation, even attempting to run for congress in 1988. He was unable to secure the democratic nomination, however, securing only 10% of the vote in the primary election. Blanton would spend his final years working as a salesman at a Ford dealership in Henderson, Tennessee. In November of 1996, Blanton would die while awaiting a liver transplant at the age of 66.

Final Thoughts

Blanton’s dramatic rise and fall, from the bottom of society to the pinnacle of Tennessee political power, to disgraced criminal and washed up car salesman is one of great Shakespearean drama. Blanton began his life with an earnest desire to serve the people, to alleviate the sufferings of poverty he once experienced. However, as Blanton accumulated power, he fell victim to greed, corruption, and party politics. His ego grew out of control and he thought himself invincible. Like Icarus, he flew too close to the sun and ultimately crashed and burned.